Relational Frame Theory (RFT) has emerged as a key development in the contextual behavioral science tradition, offering a new approach to understanding human language and cognition. In the sections that follow, we will outline the foundational ideas that define RFT, describe how it builds upon earlier behavior analytic work and explore its implications for understanding psychological processes.

Note: This is a technical explanation of RFT. For a more accessible introduction read this article.

The Nature of Verbal Events

Our work on rule-governed behavior eventually led us to a challenging realization: in some cases, the very rules people follow—no matter how rational—can become part of the problem. Trying to change this by simply offering new, logical advice often failed, because it used the same kind of verbal reasoning we were trying to loosen. This was especially true in situations where rigid adherence to rules got in the way of flexibility or well-being. To move forward, we needed a deeper understanding of how language itself works—not just the content of what people say or think, but the processes behind it. After years of exploring how rules guide behavior, we shifted our focus to the broader nature of human language.

Stimulus Equivalence

We began working on derived stimulus relations and stimulus equivalence as a jumping-off point for an empirical attack on the essence of human verbal behavior. The fundamental phenomenon of stimulus equivalence is usually examined in what is called a matching-to-sample paradigm. In a visual example of such a paradigm, an unfamiliar visual stimulus (such as a graphical squiggle or a series of three consonants) is presented at the top of a computer screen. A set of perhaps three novel comparison stimuli is provided. The subject is then reinforced for selecting the “correct” comparison stimuli. Comparison stimuli are arbitrarily assigned as either correct or incorrect by the experimenter. There is no formal property of the stimuli that provides a basis for correctness. In this way, the subject is taught that given stimulus A1 (we are using the label “A1” for ease of understanding, but in fact the actual stimulus would be an arbitrary one such as a graphical squiggle) and comparisons B1, B2, and B3, to pick B1, not B2 nor B3. In further training, the subject may be taught that given the stimulus A1 and another set of comparisons, C1, C2, and C3, to pick C1. The stimuli that are incorrect would be correct in the presence of other samples. Given stimulus A2 and the comparisons B1, B2, and B3, for example, the subject would be taught to pick B2, not B1 or B3.

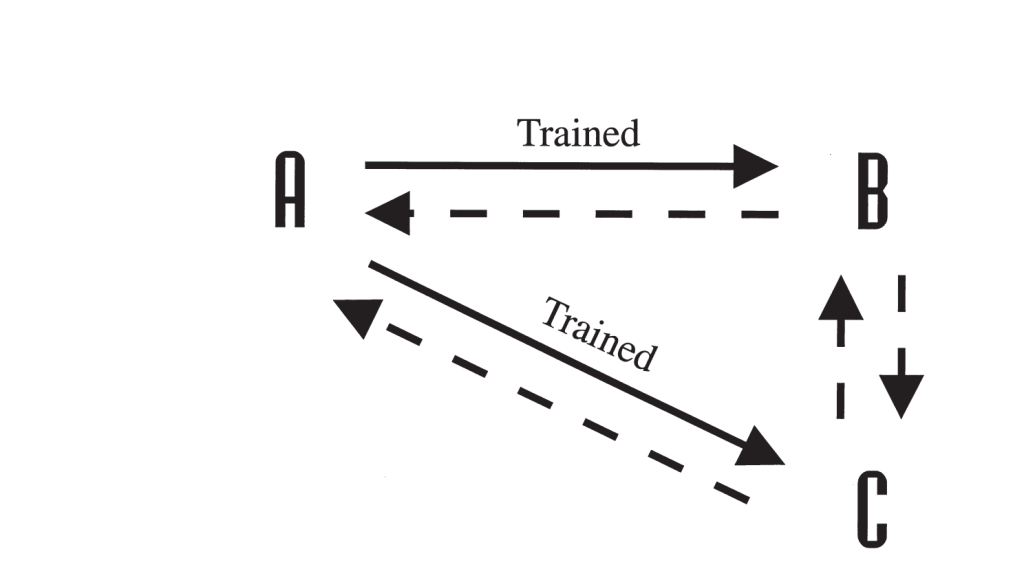

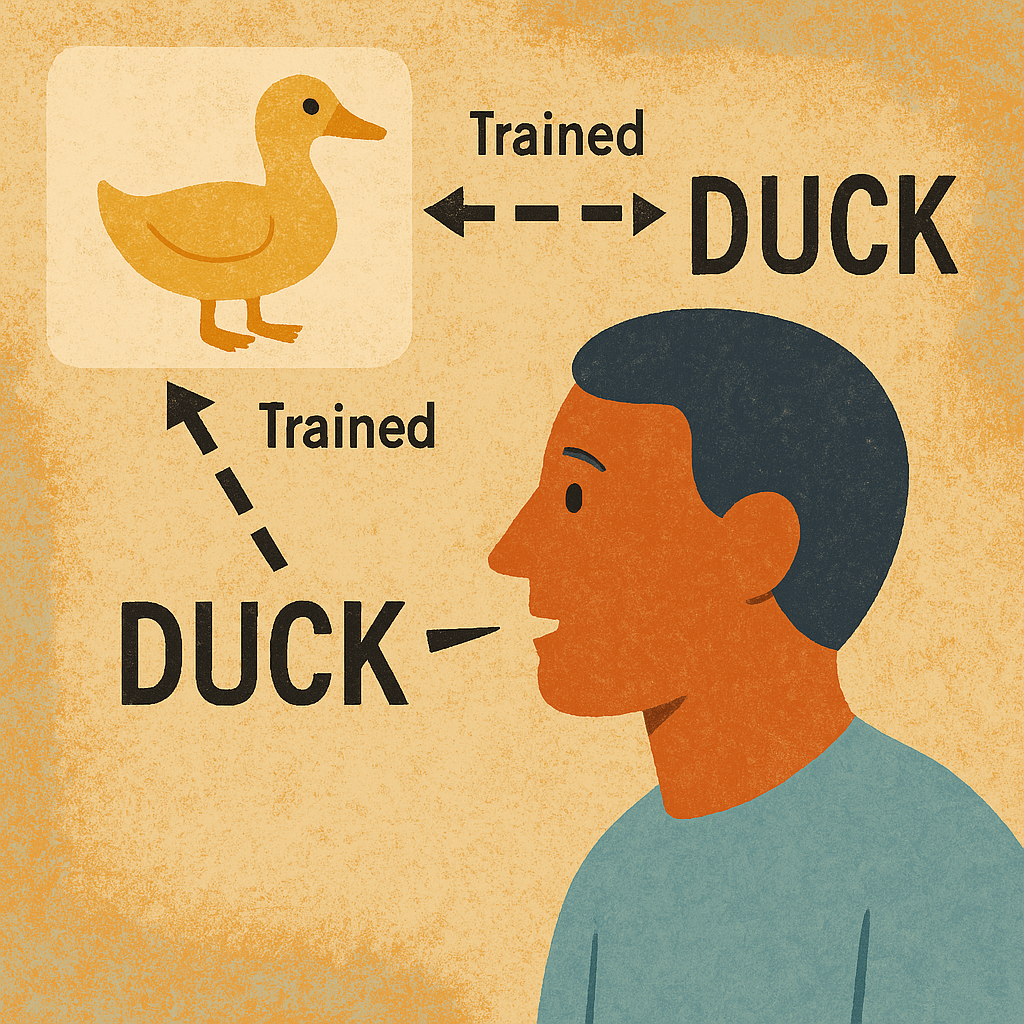

Such conditional discriminations can be trained in any complex organism (e.g., rats, pigeons, or people). What is striking, however, is the derived performances that result in people but seemingly not in nonhumans. A nonhuman exposed to a trial in which B1 is presented for the first time as the sample stimulus, with the previous samples—A1, A2, and A3—as the comparisons, will select A1 only at the level of chance. The discriminations taught do not automatically reverse. Verbally competent humans, on the other hand, will readily select A1 without explicit feedback or training, exhibiting what is called “symmetry.” This occurs in human children as young as 17 months old (Lipkens, Hayes, & Hayes, 1993). Similarly, if presented with a trial with B1 as the sample and C1, C2, and C3 as the comparisons, humans will readily select C1, whereas nonhumans will again respond at chance levels. Note that in this equivalence trial, the subject has never before even seen the B and C stimuli together at the same time. We can think of equivalence classes this way: Train two sides of a triangle in any one direction; as a result, humans will show all sides in all directions.

FIGURE 2.2. An example of stimulus equivalence. Training is indicated by the solid arrows, and derived stimulus relations are indicated by the dashed arrows.

The basic arrangement is shown in Figure 2.2. Training two stimulus relations to a nonhuman generates two stimulus relations. Training two stimulus relations to a human generates six stimulus relations. As a result, there is an inherent economy of learning that gives humans a great advantage over nonverbal organisms. Equivalence classes provide a ready model of word-referent relations. If a child is taught to relate a written word to an oral name, and a written word to a class of objects, then all the other relations will emerge without further training. This is part of what we mean when we say that a child “understands” what a word means. The child, without explicit training in this specific case, will be able to say the name of the object, for example.

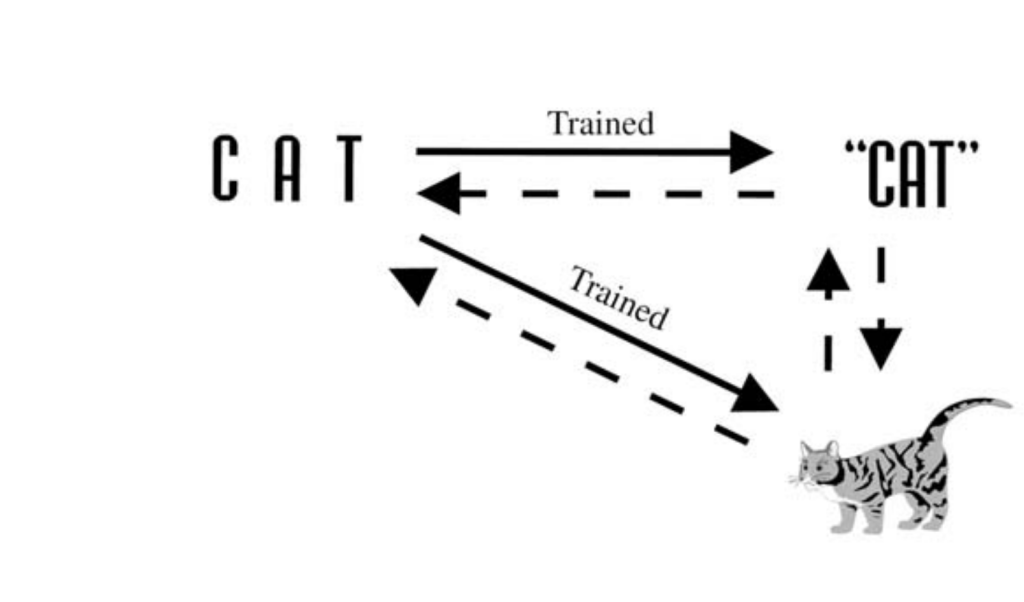

FIGURE 2.3. How derived stimulus relations establish literal meaning. Training is indicated by the solid arrows, and derived stimulus relations are indicated by the dashed arrows.

This arrangement is shown in Figure 2.3. Suppose a child is taught that the three letters C – A – T are called “cat.” Furthermore, the child is taught that these three letters go with a class of furry animals with four legs and a tail who meow. So far we have two stimulus relations (written word–oral name; written word–class of objects). But now we show such an animal to the child and say, “What is this?” The child will probably say “a cat.” Similarly, if we say, “Where is the cat?” the child may point toward a furry animal with four legs and a tail. These performances are represented by the vertical dashed arrows in Figure 2.3. Although almost all humans (except the most severely retarded) show such derived relations readily and very early, after 20 years of searching there are still no convincing data for such an ability in nonhumans. This remarkable behavioral performance opens up whole new ways of establishing and altering behavior. What makes stimulus equivalence clinically relevant is that functions given to one member of an equivalence class tend to transfer to other members. Let us consider a simple example. Suppose the child trained in the way shown in Figure 2.3 has never before seen or played with a cat. After learning the word → object, and word → oral name relations, the child can derive four additional relations: object → word, oral name → word, oral name → object, and object → oral name. Now suppose that the child is scratched while playing with a cat. The child cries and runs away. Later the child hears Mother saying, “Oh, look! A cat.” Now the child again cries and runs away, even though the child was never scratched in the presence of the word.

Relational Frame Theory Equivalence

Relational Frame Theory Equivalence is a beginning model of word-referent relations, but it is not enough to explain the functions of verbal rules nor the complexity of human language. Relational Frame Theory (RFT) (Hayes, 1991; Hayes & Hayes, 1989, 1992; Hayes & Wilson, 1993; Hayes & Barnes, 1997) expands stimulus equivalence into the larger, more general case.

RFT begins with the idea that organisms can learn to respond relationally to various stimulus events. This is not an entirely odd idea inasmuch as we know that nonarbitrary stimulus relations can be learned by almost any complex organism (Reese, 1968). For instance, a rat can be trained to turn down the least brightly lit of two alleys. With sufficient history, such a rat could negotiate a maze in which it was required to choose directions based on the relative brightness of the alternatives, even if the particular levels of illumination had never been used before. We reasoned that if such nonarbitrary stimulus relations can be learned, perhaps subjects can also learn to treat arbitrary stimulus combinations as if they are related in particular ways. Because the pairs would be arbitrary, these relational responses would have to be under the control of cues other than simply the form of the related events. For example, could humans learn to relate the two words dim and bright much as they would an actual dim and bright stimulus, given some contextual cue that would define the comparative relation between them?

Such contextual control has often been demonstrated in stimulus equivalence research (Bush, Sidman, & deRose, 1989; Gatch & Osborne, 1989; Wulfert & Hayes, 1988), and it is obvious in natural language. The spoken word bat has a different meaning when a person is in a dark cave, as opposed to being at a baseball game.

This simple idea has wide implications. It means that it may be possible to learn to relate events arbitrarily and in a large number of ways, and then to apply these learned relational patterns to new stimuli based simply on the proper arrangement of contextual cues. In this perspective, stimulus equivalence is a learned class of behaviors, and it is only one of many kinds of derived stimulus relations. For example, stimulus relations such as more–less, before–after, opposite, or different are all examples of learned and arbitrarily applicable stimulus relations.

This more flexible concept views the action of relating stimuli as a kind of learned overarching behavioral class. Such classes have been identified before in behavioral psychology. Generalized imitation can be viewed as an example of such a class. If a generalized imitative repertoire has been trained (the basic components of which seem to be inborn), a virtually unlimited variety of response topographies can be substituted for the topographies used in the initial training (e.g., Baer, Peterson, & Sherman, 1967; Gewirtz & Stengle, 1968). A child who has learned to smile when a mother smiles, and clap when the mother claps, may also now wave when the mother waves, even though this specific topography has never been trained.

There are other examples of these kinds of learned overarching behavioral classes, such as learned creativity (Pryor, Haag, & O’Reilly, 1969) or learned randomness (Neuringer, 1986; Page & Neuringer, 1985). There are three main properties of relating as a learned class of behavior. First, such relations show mutual entailment. That is, if a person learns in a particular context that A relates in a particular way to B, then this must entail some kind of relation between B and A in that context. For example, if Alan is said to be larger than Bob, then Bob must be smaller than Alan. We will also call this property “bidirectionality.” Second, such relations show combinatorial entailment: If a person learns in a particular context that A relates in a particular way to B, and B relates in a particular way to C, then this must entail some kind of mutual relation between A and C in that context. For example, if Bob is larger than Charlie, then Alan is also larger than Charlie. Finally, such relations enable a transformation of stimulus functions among related stimuli. If you need a person to arm wrestle an enemy, and Charlie is known to be valuable, Alan is probably even more valuable. Derived stimulus functions of this kind have been demonstrated with conditioned reinforcing functions (Hayes, Devany, et al., 1987; Hayes, Kohlenberg, & Hayes, 1991), discriminative functions (Hayes, Devaney, et al., 1987), elicited conditioned emotional responses (Dougher, Augustson, Markham, & Greenway, 1994), and extinction functions (Dougher et al., 1994). Verbal relations can even actively transform functions based on the relational network involved (see Dymond & Barnes, 1995, 1996, for empirical examples). For example, suppose a person is told that a tone precedes a shock and a buzzer will follow it. The tone will now elicit arousal. The buzzer will occasion calm.

We now know that once stimulus relations are derived, they are extraordinarily difficult to break up, even with direct contradictory training (Saunders, 1989). Furthermore, even if they are changed by direct training, they will later show “resurgence” if the new pattern itself no longer works (Wilson & Hayes, 1996). In other words, once verbal relations are derived, they never seem really to go away. You can add to them, but you cannot really eliminate them altogether. Even if they disappear functionally, they may reappear if newly learned verbal behavior is disrupted.

We also now know that one of the major consequences for derived relational responding is “sense making.” Even without any external feedback, subjects will create orderly stimulus relations between arbitrary stimulus sets (Saunders, 1989), and one of the most effective ways to prevent the derivation of stimulus relations is the use of occasional incoherent and confusing tests items (Leonhard & Hayes, 1991). Once we learn how to derive relations between events, we do so constantly as long as we are able to make order of our world by doing so. Whereas direct shaping gradually establishes generalized patterns of responses, the formation of sets of derived stimulus relations is more categorical—more all or nothing. Elements are either in or out, in a given context.

We are now ready to define the term relational frame. This term is used to specify a particular pattern of contextually controlled and arbitrarily applicable relational responding involving mutual entailment, combinatorial entailment, and the transformation of stimulus functions. This pattern of responding is established by a history of differential reinforcement for producing such relational response patterns in the presence of relevant contextual cues, not on a history of direct nonrelational training with respect to the stimuli involved (see Hayes, 1991, and Hayes & Hayes, 1989, 1992, for further elaboration). Although the term relational frame is a noun, it always refers to the situated act of an organism. That is, the organism does not respond to a relational frame. It responds to historically established contextual cues—and the response is to frame these events relationally. Although framing relationally may be preferred from a technical perspective (see Hayes & Hayes, 1992, and Malott, 1991, for further discussion), we will use the less cumbersome noun form. Relational Frame Theory is still new, but there is an array of basic behavioral evidence in support of it (see Hayes & Barnes, 1997). Even quite young children can show astoundingly complex forms of behavior based on a small number of trained relational responses (Barnes, Hegarty, & Smeets, 1997). For example, a relational network composed of just a dozen trained uni-directional relations will yield hundreds of derived relations.

So What Is a Verbal Event?

Having defined relational frames, we are finally ready to define a verbal event. A verbal event is simply one that has its psychological functions because it participates in a relational frame. This elegantly simple definition brings good order to the line of cleavage between verbal and nonverbal events. For instance, verbal rules are “verbal” because their effects depend on their elements being in relational frames. Gestures, signs, and pictures are “verbal” if their effects depend on their participation in relational frames, but they are “nonverbal” if that is not true. It is a core position of Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) that the literal nature of human language is based on relational frames. Thus, weakening the literal functions of language requires the weakening of relational frames in specific contexts.

Suppose I tell you, “After you read this book, you will understand ACT a little differently.” This sentence has meaning because the various elements of the sentence are in relational frames with other events and because the elements serve as cues for new relational actions and the functions that can be transformed by them.

“After” is a relational term. It is in an equivalence class with a particular relational frame (namely, the temporal frame of before and after) and serves as a cue for the application of that relational frame. That term puts “read this book” before the consequence of that action, namely, what you understand about ACT. By now “ACT” is in an equivalence class with “Acceptance and Commitment Therapy” for readers. The phase “you read this book” is also a sequence of stimuli in equivalence classes that specify who and what are being spoken about (e.g., “you” is in an equivalence class with the conscious organism gazing at these pages), but “read” further serves as a particular cue that brings a previously established psychological function to bear on what was just described. Thus, this part of the sentence specifies an antecedent condition (this book) and a function to apply to that condition (you read). “You will understand ACT a little differently” also has stimuli in equivalence classes (“understanding” is in an equivalence relation with the very act of deriving stimulus relations) and stimuli that serve as relational cues (“little” and “differently”). The phrase establishes a relation of difference between the derived relations that exist now in the reader and those that will follow reading, and limits those difference relations by the comparative relation of big and small, or more and less.

Given this reformulation, the sentence is a contingency specification. It tells the reader how to respond to an antecedent and what to expect as a consequence of that action. Several different relational frames (coordination or equivalence; difference; comparison; temporal relations) are applied to a set of terms that are already in equivalence classes with various events, and contextual cues are provided for specific psychological actions that are to be brought to bear on the situation.

If you have derived the stimulus relations properly (if you understand the sentence), we could enter into the resulting relational network in any one of several ways. We could ask, for example, “What will happen after you read the book?” or “When will your understanding be different?” or “How different will it be?” If the relational network has been properly established, all of these questions will be answered readily, even though none of them has been trained directly in this instance. These relational actions working together is what it means to “understand” a rule. Whether or not the rule is followed is a different matter. “After you read this book, you will understand ACT a little differently” could function as a track, for example, and if the reader has the proper history with such rules, it probably will. Or it could function as a ply—for example, the reader might now be expected to understand things differently by an instructor who is aware of the examples in the book, and the reader may modify his or her behavior for that reason. All of these actions on the part of the listener or reader are “verbal” by our definition, because all of these actions depend on relational frames. In the same way, a speaker is speaking verbally and “meaningfully” when the act of speaking is dependent on a relational frame. It is worth noting that, defined in this way, most human behavior is verbal, at least to a degree. If we look at a tree and see a T-R-E-E, a “plant” that “photosynthesizes” and has particular “cell structures” and so on—then the tree is functioning as a verbal stimulus for the observer. It is hard for humans to avoid the derived nature of stimulus functions in their world, because even “nonverbal” stimuli quickly become verbal in part when they enter into relational frames. Much of what we know we “know” only verbally.

We previously noted that human suffering seems to be based in part on verbal knowledge. We described the biblical story of Adam and Eve as a story with that main theme. Relational Frame Theory leads to the same conclusion. We will discuss that repeatedly throughout the book, but a brief description of the position seems worthwhile now. Verbal and Nonverbal Knowing The word know in English has an interesting etymology. It comes from two quite distinct Latin roots: gnoscere, which means “knowing by the senses,” and scire, which means “knowing by the mind.” In the usual human conception, knowing by the mind (knowing things consciously) is familiar and safe. It is unconscious, nonverbal processes that seem strange and hard to understand. Scientifically, it is the other way around. Knowing by direct experience, or contingency-shaped behavior, is something psychologists understand quite well. Verbal knowledge, or “knowing by the mind,” is strange and hard to understand.

Relational Frame Theory views verbal knowledge as the result of networks of highly elaborated and interconnected derived stimulus relations. That is what “minds” are full of. These relational responses enable forms of activity that could not occur otherwise. It is some of these activities that are at the root of human suffering.

Let us consider an example. Almost all schools of psychology have emphasized the importance of self-knowledge. For example, B. F. Skinner suggested, “Self-knowledge has a special value to the individual himself. A person who has been ‘made aware of himself’ is in a better position to predict and control his own behavior” (Skinner, 1974, p. 31). We agree, but these benefits depend on relational frames. Because of the mutual entailment quality of relational frames, when a human interacts verbally with his or her own behavior, the psychological meaning of both the verbal symbol and the behavior itself can change. This bidirectional property makes human self-awareness useful, but it also makes it potentially aversive and destructive. A pigeon can easily be taught that kind of self-awareness or selfknowledge. For example, suppose we teach a pigeon (using food as a consequence) to peck one key after it has been shocked and another after it has not been shocked. We are, in effect, asking the pigeon whether it has been shocked, and the bird is “answering.” These answers are not, however, bidirectionally related to the original condition. For that reason, the bird will as readily “report” about the shock as it will the absence of shock. These reports, after all, lead to food, not shock.

Humans are quite different, because verbal self-awareness or self-knowledge (using our definition of verbal) is bidirectionally related to the original condition. Thus, for example, even the very word shock will carry with it some of the aversive functions of shock itself. For the verbally competent human, the word shock and the actual shock exist in an equivalence class and therefore share some stimulus functions. This is why humans often cry when reporting past hurts and traumas even (or perhaps especially) if the report has never been made before. The crying comes because the report is mutually related to the event itself, not because the report itself has been directly associated in the past with aversive events. In addition, changes that are made in the functions of the verbal report can also change the functions of stimulus conditions similar to that being reported. For example, imagine someone feels pain when talking about a difficult experience with their father. Over time, if they keep talking about it—either in therapy or even just thinking about it—the emotional pain can start to lessen. And as that happens, how they feel about their father may also begin to shift. This kind of change wouldn’t happen in animals that don’t use language, but it does in humans because of how our minds work with words and meaning.

This two-way connection—between how we talk about something and how we feel about it—is at the heart of many therapy approaches. It’s why just remembering or imagining a painful event can actually help people heal from it. The ability to reflect on ourselves and our past gives us the power to change how we live. But it also creates struggle, because painful thoughts and memories can feel just as real as the original experience. Naturally, we try to avoid these unpleasant feelings. That’s one of the downsides of having a verbal, thinking mind.

SUMMARY: IMPLICATIONS OF FUNCTIONAL CONTEXTUALISM, RULE GOVERNANCE, AND RELATIONAL FRAME THEORY

Some of the insights offered by rule governance and relational frame theory fit with the known clinical functions of language and cognition. In these areas, the work on derived stimulus relations provides a basic account and shows how primitive and early these processes are, being demonstrable even in human infants but so far not at all in nonhumans. In other areas, however, the insights are not common sense.

The following 10 generalizations can be made, based on the existing literature we have discussed so far.

Verbal relations dominate

1. Verbal relations in humans are primitive, dominant, and fundamental. They occur early and readily, even in infants. The basic behavioral processes involved may not occur in nonhumans and certainly do not occur as readily as in humans.

2. Much of the human world becomes verbal in our sense. Verbal stimuli include far more than words. Even the most obviously “nonverbal” event is probably at least in part functionally verbal for humans. We will call this “verbal dominance.”

Context Is the Key

3. Verbal relations are contextually controlled. In some contexts they occur more than in others.

4. The stimulus functions that are transformed by verbal relations are also contextually controlled, and thus the behavioral impact of verbal relations is contextual, not mechanical. In some contexts, symbols and referents can virtually fuse together. We will call such context “the context of literality,” and the effect we will call “cognitive fusion.” In other contexts, the verbal relations exist but few actual stimulus functions are transferred among them.

Self-Knowledge Is a Two-Edged Sword

5. The bidirectionality of verbal relations makes self-knowledge useful, but it also makes self-criticism or self-avoidance almost inevitable. We will call this “the principle of bidirectionality.”

Changing Verbal Relations through Process or Content Differs

6. Verbal relations can occur with minimal continuing environmental support. Contexts that support sense making (in which there are payoffs for being able to draw stimuli into a coherent network of stimulus relations) are enough to maintain verbal behavior, but these direct contexts are amplified by the way the verbal community demands reasons and rationales for behavior. We will call this latter context the “context of reason giving.” Contexts that do not support sense making are effective means of loosening verbal relations. This is a primary cornerstone of many ACT techniques.

7. Changing verbal relations by adding new verbal relations elaborates the existing network, it does not eliminate it. At the level of content, verbal relations work by addition, not by subtraction. Because sense making, left to its own devices, is a common context, verbal networks are ever more elaborated. The main way to weaken verbal relations effectively is to alter the context supporting the verbal process, not by focusing on the verbal content.

Rules Are Necessary and Often Useful, but They Are Tricky and Dangerous

8. Verbal rules induce relative insensitivity to the direct consequences of responding.

9.This becomes a bigger problem when we follow rules just to please others,, when we follow rules that haven’t been tested in real life, or when we chase distant or vague goals. In therapy, people often keep following these kinds of rules even when they’re clearly not working anymore.

10. These different ways of following rules—doing what we’re told (pliance), following useful instructions (tracking), or following values and goals (augmenting)—develop over time. All of them are important, but as we grow, some become less useful in everyday life. The ACT approach helps people recognize when rule-following is getting in the way, and teaches how to shift toward more flexible, helpful ways of responding based on what really matters in the moment.

To read more:

Hayes, Steven C. Acceptance and commitment therapy : an experiential approach to behavior change / Steven C. Hayes, Kirk D. Strosahl, Kelly G. Wilson.

ISBN-10: 1-57230-481-2 ISBN-13: 978-1-57230-481-9 (hardcover)

ISBN-10: 1-57230-955-5 ISBN-13: 978-1-57230-955-5 (paperback)

References

Baer, D. M., Peterson, R. F., & Sherman, J. A. (1967). The development of imitation by reinforcing behavioral similarity to a model. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior, 43, 553–566.

Barnes, D., Hegarty, N., & Smeets, P. M. (1997). Relating equivalence relations to equivalence relations: A relational framing model of complex human functioning. Analysis of Verbal Behavior, 14, 57–83.

Bush, K. M., Sidman, M., & deRose, T. (1989). Contextual control of emergent equivalence relations. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior, 51, 29–45.

Chiles, J., & Strosahl, K. (1995). The suicidal patient: Principles of assessment, treatment and case management. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press.

Dougher, M. J., Augustson, E., Markham, M. R., & Greenway, D. E. (1994). The transfer of respondent eliciting and extinction functions through stimulus equivalence classes. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior, 62, 331–351.

Dymond, S., & Barnes, D. (1995). A transformation of self-discrimination response functions in accordance with the arbitrarily applicable relations of sameness, more-than, and less-than. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior, 64, 163–184.

Dymond, S., & Barnes, D. (1996). A transformation of self-discrimination response functions in accordance with the arbitrarily applicable relations of sameness and opposition. Psychological Record, 46, 271–300.

Follette, W. C. (1995). Correcting methodological weaknesses in the knowledge base used to derive practice standards. In S. C. Hayes, V. M. Follette, R. M. Dawes, & K. E. Grady (Eds.), Scientific standards of psychological practice: Issues and recommendations (pp. 229–247). Reno, NV: Context Press.

Gatch, M. B., & Osborne, J. G. (1989). Transfer of contextual stimulus function via equivalence class development. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior, 51, 369–378.

Gewirtz, J. J., & Stengle, K. G. (1968). Learning of generalized imitation as the basis for identification. Psychological Review, 75, 374–397.

Hayes, S. C. (1989). Nonhumans have not yet shown stimulus equivalence. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior, 51, 385–392.

Hayes, S. C. (1991). A relational control theory of stimulus equivalence. In L. J. Hayes & P. N. Chase (Eds.), Dialogues on verbal behavior (pp. 19–40). Reno, NV: Context Press.

Hayes, S. C., & Barnes, D. (1997). Analyzing derived stimulus relations requires more than the concept of stimulus class. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior, 68, 235–270.

Hayes, S. C., & Hayes, L. J. (1989). The verbal action of the listener as a basis for rule-governance. In S. C. Hayes (Ed.), Rule-governed behavior: Cognition, contingencies, and instructional control (pp. 153–190). New York: Plenum.

Hayes, S. C., & Hayes, L. J. (1992). Verbal relations and the evolution of behavior analysis. American Psychologist, 47, 1383–1395.

Hayes, S. C., & Wilson, K. G. (1993). Some applied implications of a contemporary behavior-analytic account of verbal events. The Behavior Analyst, 16, 283–301.

Hayes, S. C., Devany, J. M., Kohlenberg, B. S., Brownstein, A. J., & Shelby, J. (1987). Stimulus equivalence and the symbolic control of behavior. Mexican Journal of Behavior Analysis, 13, 361–374.

Hayes, S. C., Kohlenberg, B. S., & Hayes, L. J. (1991). The transfer of specific and general consequential functions through simple and conditional equivalence classes. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior, 56, 119–137.

Leonhard, C., & Hayes, S. C. (1991, May). Prior inconsistent testing affects equivalence responding. Paper presented at the annual meeting of the Association for Behavior Analysis, Atlanta, GA.

Lipkens, R., Hayes, S. C., & Hayes, L. J. (1993). Longitudinal study of derived stimulus relations in an infant. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 56, 201–239.

Malott, R. W. (1991). Equivalence and relational frames. In L. J. Hayes & P. N. Chase (Eds.), Dialogues on verbal behavior (pp. 41–54). Reno, NV: Context Press.

Neuringer, A. (1986). Can people behave “randomly”? The role of feedback. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 115, 62–75.

Page, S., & Neuringer, A. (1985). Variability is an operant. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Animal Behavior Processes, 11, 429–452.

Pryor, K. W., Haag, R., & O’Reilly, J. (1969). The creative porpoise: Training for novel behavior. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior, 12, 653–661.

Reese, H. W. (1968). The perception of stimulus relations: Discrimination learning and transposition. New York: Academic Press.

Saunders, K. J. (1989). Naming in conditional discrimination and stimulus equivalence. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior, 51, 379–384.

Skinner, B. F. (1974). About behaviorism. New York: Vintage Books.

Wulfert, E., & Hayes, S. C. (1988). The transfer of conditional sequencing through conditional equivalence classes. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior, 50, 125–144.

Thanks for posting this excerpt, very useful in understanding RFT!

LikeLike